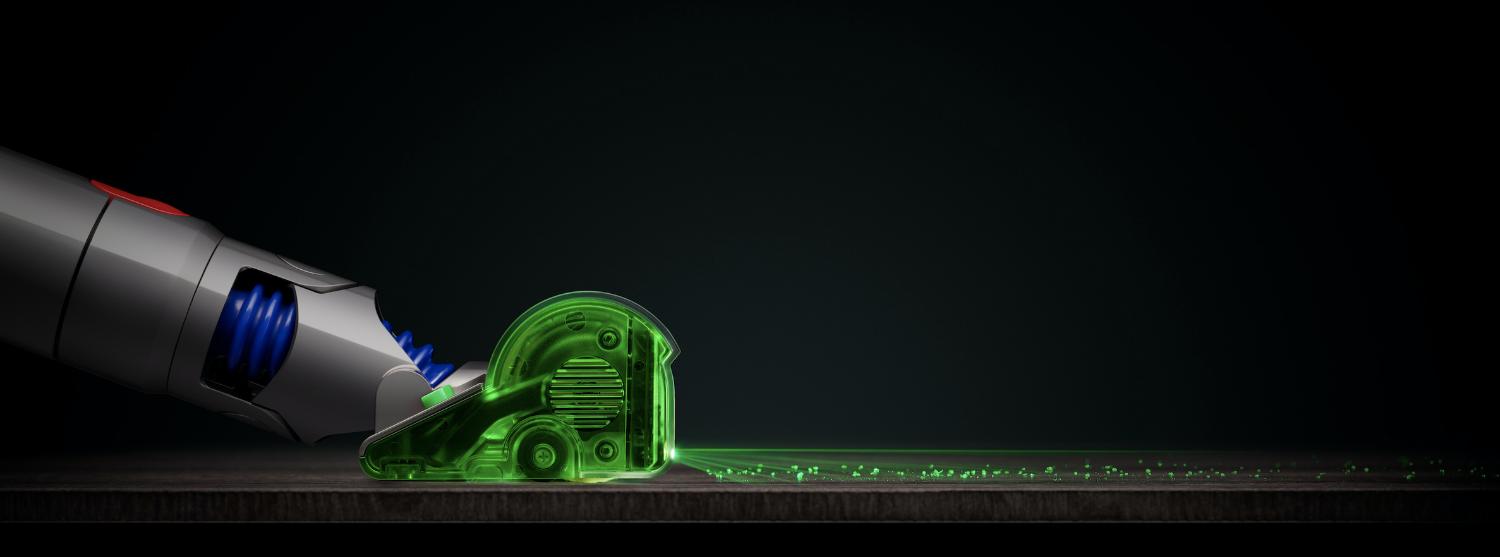

Behind the laser

Dyson V15 Detect laser explained: how Dyson engineers made the invisible, visible

-

"It was one of those shower moments," says Stephen Dimbylow, Head of New Product Innovation for Floorcare at Dyson, from inside D9, Dyson's top-secret laboratory for research and development in Malmsbury, UK. "I don't know how it happened, but I remember my dad telling me back in the day, if you get your eye right down to floor level, you can spot whatever you've lost because it pops up above the surface of the floor. So, one day, I thought, maybe if we combine a low-level laser, we can light up the dust on the floor?" he says excitedly.

While Dimbylow and his team had been looking into the effect of illuminating surfaces to reveal hidden dust for years, it was a rough experiment using a child's laser pen that spawned the thinking behind Dyson's most powerful and intelligent cordless vacuum, the V15 Detect. "I brought that laser into the lab and started to shine it on the floor, moving it from side to side really quickly to illuminate a patch of dust...then we tried a low-level disco laser light and that was amazing. You could see little embers of green glow from metres away, it was staggering," says Dimbylow.

-

Beyond the initial test and proof of concept, Dimbylow and his team focused on refining the laser light beam, trying different lenses and creating a control box and a rig on which they could mount it to help create the exact profile of beam needed. "We knew it was going to be a very narrow, wide, flat beam," he explains. "When I tried the test rig, it illuminated everything that we were hoping for. You could really see where you'd been with the cleaner head." While visibly tracking vacuum cleaner progress on a carpet can be seen through the 'groomed' patches, doing the same on hard floors is more of a challenge. "With a laser, you can now track your progress on a hard floor for the first time...we were really quite blown away by that." Working through any practical concerns, Dyson engineers ensured the laser was powerful enough to illuminate microscopic dust particles but also safe enough to use in homes all around the world. "We learnt really early on that green light was much more perceivable to the human eye than red laser light - there's a spectrum that the human eye will prefer, which makes it more visible."

-

-

Preparing the new technology for production came with its own challenges. With a laser embedded into the vacuum head, heat generated by the laser's circuit board meant it needed to be cooled by the air rushing through the machine, while all of this needed to be carefully packaged into an existing vacuum head. "We didn't want to make the tool any wider and we didn't want to adjust it massively, so we knew we had such a small space to work with," he says.

To help perfect the laser beam, Dimbylow turned to Dyson's lighting team to consult on the project. Making use of the specialist software within the D9 research and development laboratory, the lighting team were able to simulate different lenses in the pursuit of a perfectly balanced light beam. With the initial research completed, the project was handed over to Dyson's product development team, who prepared the new vacuum concept for production.

While lighting has been a feature on vacuum cleaners for many years, the Dyson V15 Detect sets itself apart using focused light - in the form of a precisely-angled laser - to detect microscopic dust particles usually invisible to the naked eye. "We'd avoided the idea of just generally lighting up the floor because we didn't think it was hugely valuable. But the laser allowed us to make a difference. It allowed the light to become useful, to actually show the hidden dust - the dust that you can't see otherwise," says Dimbylow.

Now available around the world, the Dyson V15 Detect has come a long way from those early experiments with lasers on the floor of D9. "My role is hugely rewarding because you get to create these things, and then two, three or four years later, you get to see it in the market - you can see the success," he says, reflecting on the project. "Anybody can have an idea, but to show that it's a good idea takes all the effort. Some ideas you can have in an instant and then it takes five years of hard graft to bring it to life," he says with a smile.

After James Dyson made 5,127 prototypes to make his first vacuum the best it could be, Dimbylow’s approach to invention suggests not much has changed in the attitudes of Dyson engineers today. "The desire to invent better products and more effective machines is obsessional," he admits. "You think about it in the morning getting ready for work, in the evening, and whenever you're using a machine - you're always thinking about it. In fact, with any product, you get wound up by their failings and, I suppose, that's just what drives you to make them better."

Press contacts & materials

-

Jordan King

-